15/09/2023

Changes to your delivery: a whistle-stop tour of amendments to the International Group letters of indemnity

This week saw publication by the International Group of updated standard form letters of indemnity (LOI) for the first time in 10 years. This update of the LOI wordings has been informed by a review undertaken by an International Group working party, with input from charterer and owner representatives, BIMCO, and former Admiralty Court judge Sir Nigel Teare.

The following comments were first publicised during a Twenty Essex webinar on Wednesday 13 September, held as part of London Shipping Week. These have been edited; a recording of the full webinar, including these comments on the LOI changes, is available via the Twenty Essex website.

*

Two innovations merit particular note. Firstly, the revised wordings are accompanied by explanatory notes, which discuss the rationale for the changes which have made.

Second, the wordings themselves feature a prominent warning stating that the circumstances giving rise to the issue of an LOI will prejudice a member’s P&I cover, and that use of the LOI will not reinstate that cover.

The warning also emphasises the importance of being satisfied as to the financial standing of the party issuing the LOI. This is of course an important point: the value of the LOI is no greater than the substance of the party giving it, and the circumstances in which a delivery LOI typically comes into play is where one party in the sale chain has become insolvent.

The circular accompanying the revised wordings and commentary also reminds Club Members that the use of electronic bills could reduce the need to rely on LOIs. The Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 comes into effect on 20 September, and while this is not the time to comment in any detail on the 2023 Act, if goods are delivered in accordance with the terms of the contract of carriage contained in an electronic bill, it is to be expected that the carrier would obtain the same protection as if it delivered against presentation of a paper bill of lading.

Electronic bills offer the potential for reducing delays in the transfer of bills of lading along a sale chain. If the only reason for using an LOI in a paper transaction is inability to transfer the documents fast enough, that problem ought to be solved or reduced by using electronic bills.

Let us turn to the changes made to the LOI standard wording for delivery without presentation of original bills of lading.

Vessel, port, cargo & bill of lading details

The format of this section has been slightly expanded to encourage the inclusion of as much information as possible, with the intention that it should be made absolutely clear which bills of lading and cargo are covered by the LOI.

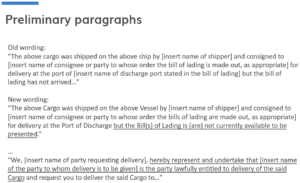

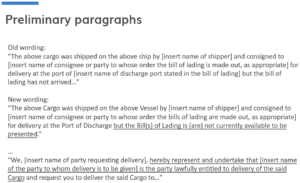

Preliminary paragraphs

In the first paragraph, a change has been made from stating that the bill has “not arrived” to “is not currently available to be presented”. This is said to more accurately cover the many reasons why the bill of lading cannot be presented. The advantage here seems to be more for the party requesting delivery than the carrier, as it reduces the risk of that party making a misrepresentation about why the bill of lading is not being presented.

In the second preliminary paragraph, a new clause has been added saying that the requesting party represents and undertakes that the party for whom delivery is to be given is the party lawfully entitled to delivery of the cargo. This is said to have been added to strengthen the promises being given by the requestor, and to make the nature of what the requestor is saying clear to them.

It seems to me that the reference to “the party lawfully entitled to delivery of the cargo” must be understood as a reference to entitlement, putting aside presentation of the bill of lading, since as against the carrier it is only a party presenting the bill of lading which has a contractual right to take delivery of the cargo from the carrier.

The circumstances in which this representation and undertaking would add materially to the other promises in the LOI are likely to be limited. However, the representation might come into play if, for example, for some reason the cargo was delivered without the promises in the LOI being triggered, but the carrier could show that the delivery was caused by a misrepresentation that the requestor was lawfully entitled to the cargo. So there are, theoretically at least, circumstances in which this materially adds to the protection of the carrier.

Paragraphs 1 and 2 have not been amended.

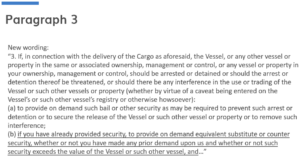

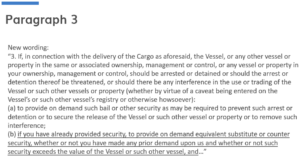

Paragraph 3: security

Paragraph 3 is substantially the same as before. However, there is new wording in subparagraph (b), which has been inserted to make it clear that if the recipient of the LOI has put up security to release the vessel, the obligation under the LOI is to replace that security or provide counter-security.

The obligation to provide replacement security had already been established by the judgment in The Bremen Max [2009] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 81 at [21]–[22].

The reference to providing counter-security reflects the fact that, in practice, once security has been put up in a given jurisdiction, it may not be possible to withdraw that security and replace it. For example, the laws of the place of arrest may require the consent of the claimant to such substitution and that may not be forthcoming, or substitution may simply not be possible under the rules of the court in that place. In those circumstances it plainly makes sense that counter-security should be provided.

The reference to counter-security could also cover the position where there is a chain of LOIs and it makes more sense to have counter-security running up the chain to the carrier, rather than having one party put up security, such as the party at the bottom of the chain.

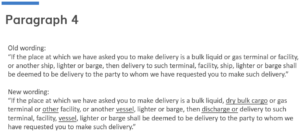

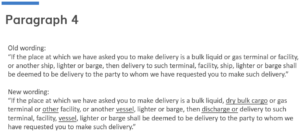

Paragraph 4: deemed delivery

Under the old wording, this paragraph was limited to bulk liquid or gas terminals or vessels. The new wording has two innovations.

Firstly, a reference has been inserted to “dry bulk cargo”, which makes this deeming provision potentially applicable to cargoes other than liquid and gas cargoes.

The notes draw attention to the fact that delivery is deemed to occur even if the cargo becomes an indistinguishable part of a larger bulk upon discharge. However, save in relation to dry bulk cargoes, there is no change in the language which relates to this.

The extension of the paragraph to delivery to a designated dry bulk cargo terminal or facility is potentially important. The possible issues that may arise in determining when and how a cargo was delivered lead to a risk that delivery ultimately did not occur in the manner requested in the LOI. That risk would be reduced for dry bulk cargoes if the request specified the relevant terminal or facility.

Second, the addition of the word “discharge” makes it clear that deemed delivery can occur for the purposes of the paragraph even if the carrier has not in fact divested itself of control of the cargo by discharging it.

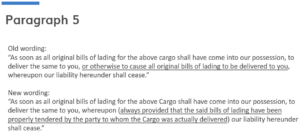

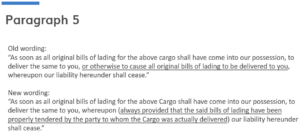

Paragraph 5: bills of lading

Of the two changes in this paragraph, the more significant is the newly inserted wording in parentheses. What the explanatory notes say about this is: “This paragraph has been amended to make it clear that the LOI obligations only come to an end if the bills of lading ultimately reach the party that took delivery of the cargo, and are thus accomplished.”

This amendment appears to be intended to ensure that the LOI is only discharged by transfer of the bills of lading to the carrier if the bill has first come into the hands of the party that took delivery. This in turn seems to be based on the proposition that a bill of lading becomes spent if the party which took delivery subsequently becomes the holder of the bill.

In terms of discharge of the contract of carriage by performance, the carrier’s breach occurs when it delivers without presentation of the bill, and in my view that breach is not wiped out if the carrier is subsequently presented with the bill by the party that took delivery.

In Barber v Meyerstein (1870) LR 4 HL 317 at [33], Lord Hatherley said that the bill of lading exhausted its role as a symbol of the goods once the person with the right to demand the property takes possession of the bill of lading. However, that principle would not apply if the party who took delivery of the goods and subsequently tendered the bill of lading to the carrier was not the party lawfully entitled to possession of the goods.

It is also arguable that when Lord Hatherley spoke of the bill of lading exhausting its role, he was referring to it being “spent” in the common law sense, that is, that it no longer performs its document of title function in transferring constructive possession of the goods to which the bills of lading relate.

Under COGSA 1992, right of suit can be acquired under spent bills provided that the transfer occurs by virtue of a transaction effected in pursuance of any contractual or other arrangements made before the bill of lading ceased to be capable of transferring construction possession of the goods.

I therefore question whether the carrier is necessarily “off the hook” simply because the bills of lading reach the party that has taken delivery and then are presented to the carrier.

However, this may all be academic, because it is arguable that a cause of action accrues under some of the paragraphs of the LOI as soon as delivery is made without presentation of the bill of lading – for example, under the paragraph 1 obligation to indemnify against liability sustained by reason of delivering the cargo.

Insofar as Courts have considered the question, they have been dismissive of any suggestion that a provision such as paragraph 5 could discharge a liability already accrued under the LOI: see for example The Songa Winds [2018] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 47 at [66].

If that is right, then, the carrier will always have at least some rights under the LOI once it has acceded to a request to deliver without presentation of bills of lading, regardless of the possible operation of paragraph 5.

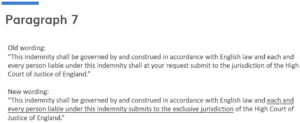

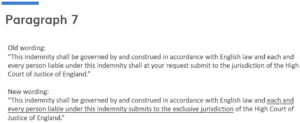

Paragraph 7: jurisdiction

The final change to highlight is in paragraph seven. The language here has been strengthened by making it clear that England is the exclusive jurisdiction rather than a jurisdiction to which the requestor is required to submit at the request of the beneficiary of the LOI.

The explanatory notes tell us that this provision was particularly carefully considered by the working group, and many different possibilities were considered in terms of jurisdiction. Under the old wording, there was simply a requirement that the requestor submit to the jurisdiction – the High Court – at the request of the carrier.

Ultimately, they have opted to retain and strengthen the choice of English law and English jurisdiction, as the exclusive jurisdiction. The rationale for doing so is sound. The recent experience of LOI litigation in the English courts shows the advantages of disputes under chains of LOIs being referred to the same court, and the willingness of the English court to make the terms of the LOI effective.